“Hey honey, before we get going inside, let me check the taps.” This is what I said to my wife as we pulled into our driveway. It was unseasonably warm that day, but it had been chilly the night before, so I was excited to see how much sap the maple tree in the front yard had given now that the sun was shining. As I walked up to the large sugar maple, the one we affectionately call “Big Sugar”, the spile shot out of the trunk and a torrent of dark brown sap came spewing out. “What in the hell?!”

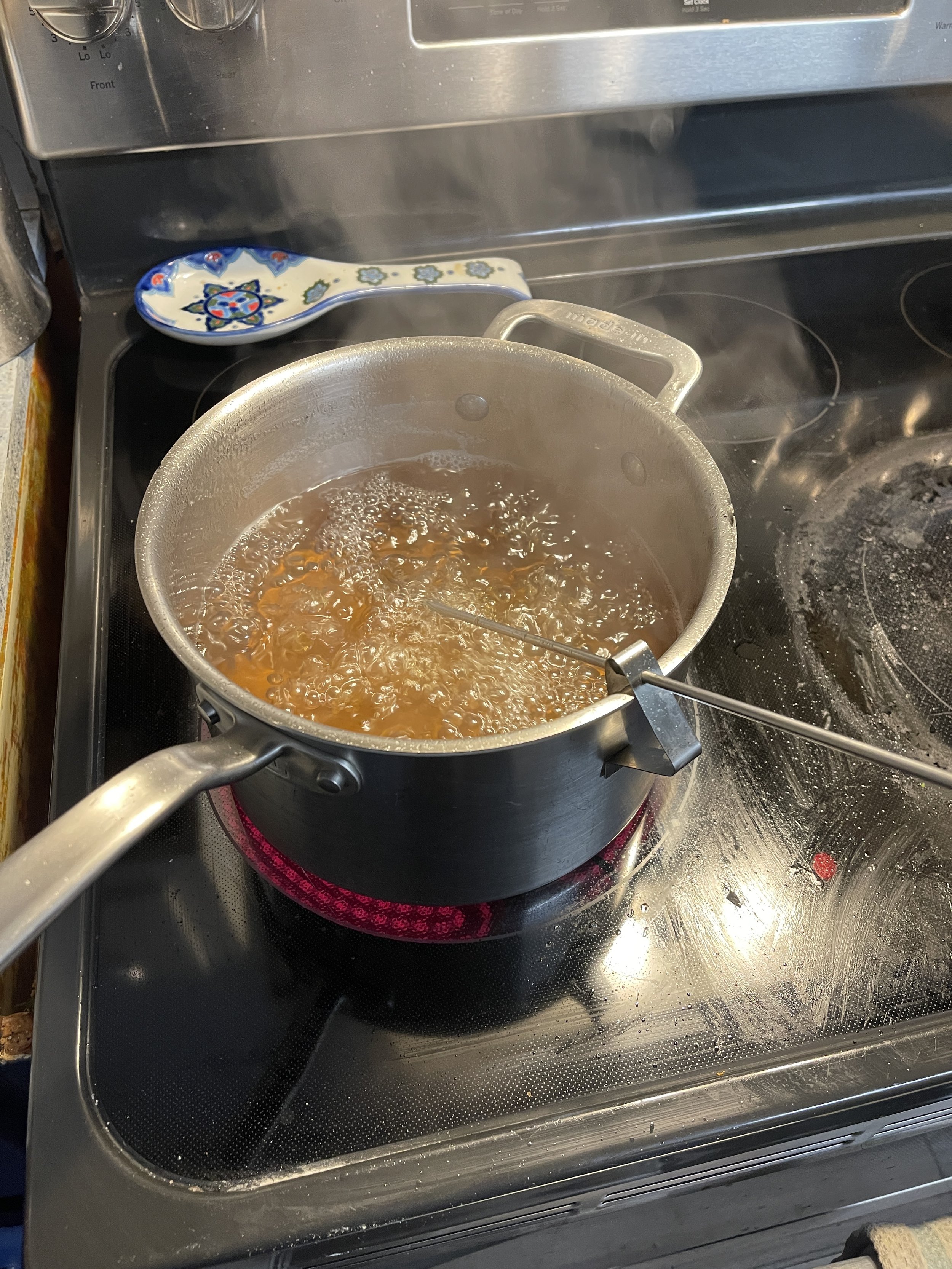

I started to panic. This wasn’t right at all. This was too much sap, and the color was all wrong. How could the tree be giving this much and still survive? Maybe this was normal? I decided to taste the sap as a scrambled to grab a bucket. “Aaaaah! That’s so bitter!” No no no no! This is bad! What could I do?! Wait…was the tree…shriveling?!

Big Sugar was dying right in front of me and I couldn’t do anything about it. My kids and wife looked on with shocked and horrified faces as Big Sugar bled out in front of us. I had left the taps in too long. I knew it! This was my fault. I had been greedy and lazy, and now the trees would die and we would suffer without the shade, oxygen, and syrup they provided.

I suddenly woke up in my bed and looked over at the clock. 6:12AM. Oh, thank goodness! It was just a dream! Or was it? I got up and looked out the window, relieved to see Big Sugar still standing strong and looking healthy. “Todays the day. We remove the taps today.”

Just the previous morning and frequently in over the last couple of days, I had been wondering how long to leave the maple tree taps in the three sugar maples and one silver maple in our yard. This was the first time I had ever tapped maples for sap to make syrup, and I wanted to do right by their gift.

I felt prepared. We had all the tools, we watched several YouTubers tutorials on maple tapping, and, most importantly, I felt that I was in the right frame of mind, had had the proper instruction, to go about this process in a way that honored the traditions of Indigenous peoples who first entered into good relations with maple trees.

I’m an ecologist by education, but it wasn’t until I started explicitly reading and listening to Indigenous people (well into my Ph.D. program) that I felt truly comfortable with a way of relating to the natural world. All the studying, classes, and research I had done up to that point had not given me the sense of “rightness” I felt when I read and heard Indigenous people talk about the ways their people interacted with other species. Robin Wall Kimmerer was and remains one of my most influential teachers, primarily through her book Braiding Sweetgrass. In this amazing work, Kimmerer draws clear and important lines of contrast and intersection between Indigenous ways of knowing and relating to non-human species, and Western European concepts of science and ecology. Through Dr. Kimmerer’s work, along with Dr. Kim TallBear’s writings and scholarship on hierarchies of life and Indigenous concepts of non-human species, I came to understand and internalize the idea that all life (as Western European science would define life) has agency and personhood.

This Indigenous world-sense challenged my socialization into hiearchal ways of classifying other beings. I was taught that the necessary harm humans caused other species was morally defensible on a scale of how closely other species mimicked human consciousness. Essentially the less “smart” and human-like an animal, the more okay it was to take their life and do with their body as we pleased. This never sat right with me, but I adopted this way of thinking because I had no alternative narrative that I found more satisfying.

Taking from the natural world was always justified from the standpoint of human superiority and the divine authority the creator bestowed upon his most wonderful creation. We were free to do with his lesser beings as we pleased, and plants, certainly qualified as lesser beings because plants are so far from humanity that they can’t possible share our concepts of mortality, pain, suffering, etc.

Perhaps my discontent with this dominant narrative of how humans should relate is this is why I cried reading the Skywoman Falling chapter in Dr. Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass. In this origin story, I had finally heard something that made sense, that didn’t contradict my instincts and experiences, that told me what my role and responsibility as a human being was. My reaction surprised me, but it was the satisfaction of a narrative that spoke to directly who I understood myself to be that motivated me to learn more.

I am not Indigenous to these lands and was not raised in community with any Indigenous people’s values or guidance beyond what some have been willing to share with non-Indigenous people. So my adoption of certain practices that have reoriented my relationship with non-human species comes with a certain measure of awkwardness. I remain open to being held accountable by Indigenous people and their judgement of whether or not I have crossed any lines.

I did, however, feel comfortable adopting the practices of asking permission from beings I was taking from and generally orienting my consciousness towards explicit gratitude for the gifts of the species (relatives) I depend on. I asked permission from each tree we tapped and waited for an answer. I got several in return.

Asking permission from “Big Sugar” with our son.

I felt there were varying degrees of assent from each tree that I asked to tap. Big Sugar, the tree in our front yard who died violently in my dreams, was the most enthusiastic about allowing me to tap them. I asked permission from them with my 5 year old; an intentional event where I hoped to teach my son something of what Dr. Kimmerer taught me. I felt like Big Sugar was pleased by this, that they felt more comfortable giving to me, knowing that the lesson of trees having personhood in the eyes of humans had a chance to live beyond one generation of non-indigenous people who now lived here. By the end of the season, Big Sugar gave about 60% of the total sap we collected; the most by far.

I understood the other trees to be less enthusiastic, ultimately giving a kind of probationary consent; allowing me to prove my worthiness this season and contemplate permission for another sugaring season over the next 10 months.

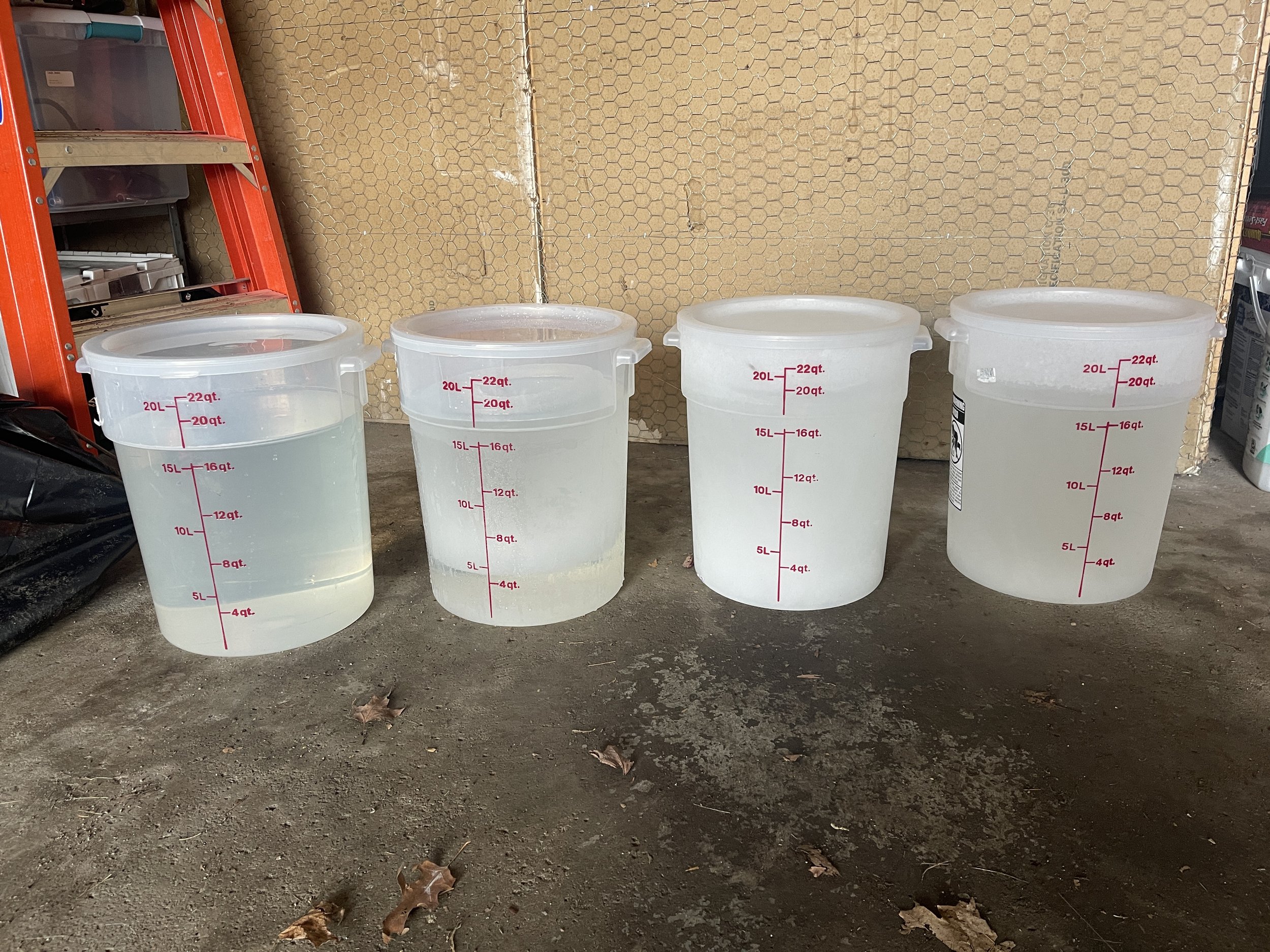

After about 18 days of sap harvest, I don’t know that I’ve earned another year’s worth of permission. Starting out, I had to drill two holes in the silver maple because the first hole was drilled incorrectly. I let sap spoil in that bucket after neglecting to remove a sow that had fallen in. I allowed another bucket to overflow in “Big Sug”, the largest and oldest (I think) maple in our yard. And finally, I let a total of three buckets spill before securing them to the tree against strong winds. I was simply lazy as all of these events could have been prevented.

My first attempt at tapping silver maple. It didn’t go so smoothly and I eventually had to drill another hole.

I will do better next year if the trees in our backyard grant their permission. What I find particularly interesting about a mindset that recognizes the personhood of other beings is what that mindset opened me up to receive and process. I dreamt of Big Sugar dying and not silver maple. Why? Perhaps the trees decided to send Big Sugar to me because they had the most friendly relationship with me. Finding empirical evidence for this hypothesis is unimportant because the results of this dream pushed me to recommit to treating these beings with more respect and care.

I have read Indigenous people describe non-human relatives answering questions and giving lessons in dreams and this is enough for me to heed any message that leads me to error on the side of sustainability and care. Moreover, my own ancestors and several friends have described similar accounts of direct messages from others in dreams. An extension of the practice of interpreting dreams to my relationship with beings who were giving of their lives, partially or completely, is not the leap into absurdity my Western European socialization thinks it is.

I pulled the taps the day of my dream, though, once again, I was neglectful and I almost went to sleep that night without pulling the taps from trees in the back yard, the trees that still weren’t sure about this human who had taken, and wasted some of, their gifts was worthy. If they so “no” next year, I will not be surprised.

Indigenous teachings, as I have understood them, about entering into relationship with other beings, requires something of gift receiver. Reciprocity. Because I have taken from my maple relatives, I must now give a gift in return. But what to give a tree that is so much older than me, both individually (the youngest of these trees is easily 65 years old) and by lineage (maples have been around since before the T-Rex, about 120 million years)? How can I give back to trees?

Dr. Kimmerer teaches that reciprocity for human beings can come from sharing stories with other humans, and treating gift givers with dignity and respect. The sharing of syrup with friends and family is not simply a transaction without context, as is most of dominant culture’s relationship with food. Sharing this syrup requires a sharing of the story of how it came to be, what it took to produce this gift from raw material, and the lessons that came with the process. The smiles that friends who’ve tasted this gift have been overwhelming to my spirit and sense of community and connection.

“Oh my goodness! This is best maple syrup I’ve ever had! Wait! Can we do this with our own trees out front?!”

And the relation of responsibility continues as I now have a responsibility with those I’ve given syrup to make sure they are good relatives to the maples that live near them. This means sharing my failures and stories of neglect along with my stories of diligence. Reciprocity is anchored in accountability, which requires honesty and vulnerability.

I have to pass on the lessons I’ve learned, the mistakes I made, and the joys I experienced so that maples feel comfortable giving. They are watching me, watching us, judging us with a spirit, I believe, of wanting all these new cultures of humans in the same good relations the first people of these lands still maintain. For millennia more humans than not did right by maple tree, and like all good friendships, no one wants them to end.

#sugaringwhileBlack